Blessed Ursuline Martyrs of Valenciennes

The Blessed Ursuline Martyrs of Valenciennes

Lecture given in Valenciennes October 23rd 2019 by Marie-Christine Joassart-Delatte

We are gathered together to commemorate the 225th anniversary of the Martyrdom of the Blessed Ursulines of Valenciennes which the Church remembers on this day.

It is a joy and a great honour for me to talk to you about their life and their heroic death. This community offers us a wonderful witness of their faith and fidelity. During the French Revolution it experienced particularly painful situations. It experienced the problems that were those of all religious communities at that time: suppression of religious communities, and their compulsory disappearance, confiscation of their property, presence of a Constitutional clergy, etc. These difficulties increased because they were established in a border area, suffering the moving tide of successive conquests during the war opposing France and Austria from 1792 on.

In this tormented situation, the Ursulines of Valenciennes chose to live, up to their death, their faithfulness to their vocation and to the commitments they had made during their religious profession, and to keep their life in community, relying on the grace of God and the strength of their Ursuline spirituality, very much influenced by a sense of martyrdom.

Eleven of them were guillotined in October 1794: five of them climbed the scaffold on October 17th; six more on October 23rd.

Subsequently, their Cause was introduced in the diocese of Cambrai in 1898 and led to the Beatification of “Mother Clotilde Angela and her Companions, in 1920”.

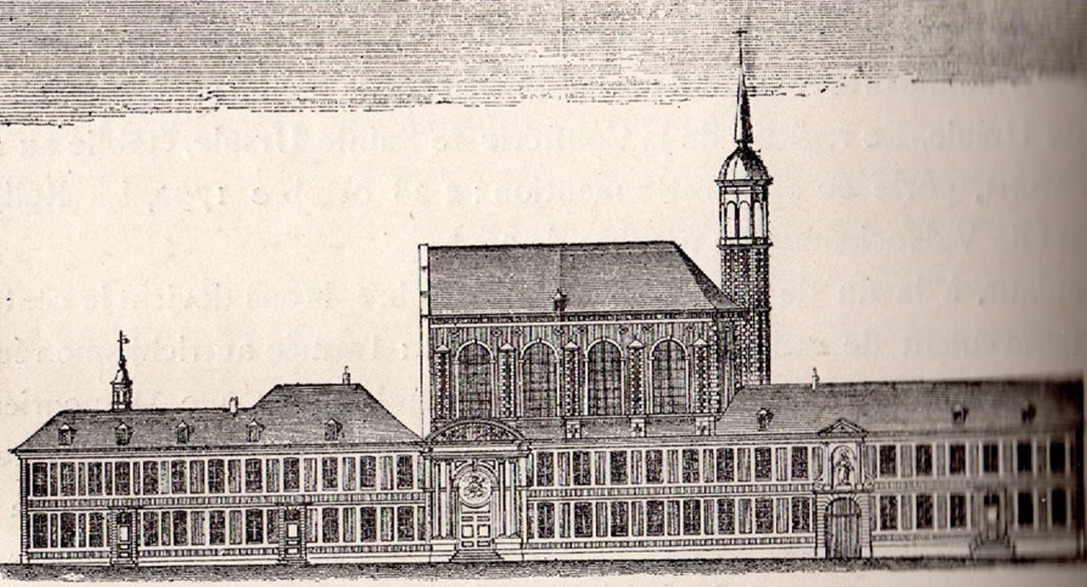

This teaching community was founded in 1654 by five Ursulines of Mons and two from Namur, thanks to the initiatives of Charlotte and Marie d’Oultreman, two notable women from Valenciennes. Their Ursuline school was the most important girls’school in Valenciennes at the time of the Revolution, and it continued to expand. In their large convent on Cardon Street, they welcomed boarders who sometimes came from far away, because of the good reputation of their boarding school which extended far beyond the borders. Above all, in their day school, they provided a free and high-quality education to several hundred girls from less affluent classes of society, giving them a Christian and elementary education. The Ursulines also provided a Christian training to young servants and workers in their Sunday school.

In 1790, they hoped for the canonization of Angela Merici. It was on August 15th, 1790, that the Papal Decree, De Tuto, was published, authorizing the canonization of Angela Merici, their foundress, who was beatified in 1768. Born in 1474 in Northern Italy, Angela Merici founded in Brescia, in 1535, under the patronage of Saint Ursula “a Company of consecrated virgins”, living in the world, eager to devote themselves to the religious and moral formation of women and little girls. Her institute was to experience an extraordinary expansion in France, during the 17th and 18th centuries, in the form of a monastic Order, with solemn vows requiring a cloistered life. There were 350 Ursuline monasteries in France, at the time of the Revolution.

Like many other Superiors, Mother Clotilde Paillot, who had just been elected Superior of the community, had a regular correspondence with Mother Schiantarelli, Postulator of the Cause of the future canonization of Angela Merici. Finally, the Ursulines in Valenciennes, while preparing this canonization, were able to become more aware of their religious identity as daughters of Saint Angela.

Religious identity was questioned in France when on February 13th, 1790, a Decree declared that

“The Constitutional Law will no longer recognize solemn vows. Consequently, the regular Orders and Congregations in which these vows are made, are and remain suppressed in France without similar ones being established in the future. All individuals will be able to leave them by declaring their intentions before the town officials, who will provide for their fate by a suitable pension.”

The Decree added, however, that nothing would be changed for the houses dedicated to public education, while waiting for the final decision. The Ursuline community was therefore not abolished by this Decree, since they were teachers, but it was clear that this was a temporary measure, allowing the State to establish the necessary structures for education, as foreseen by the Civil Constitution of the Clergy.

On the 20th of September, the Mayor went to the Ursulines to receive their declarations of intentions. The nuns were questioned individually on their desire to maintain their life in community, or take advantage of the new laws and abandon it.

Thanks to this document we know the make-up of the community: 32 sisters, including eight Lay Sisters and two Novices. All the sisters taught, except the Superior and her Assistant, the Lay Sisters, and three very old sisters. Fourteen of them devoted themselves to the public classes. (This meant very few teachers for this big day school!) and six took care of the boarders.

Mother Clotilde, the first one called to declare her intentions, stated that she “wanted to end her days in the form and the house that she had chosen”.

The two Novices expressed the same intentions “although they were unable to pronounce their vows because of the ban”, they added.

The two Novices expressed the same intentions “although they were unable to pronounce their vows because of the ban”, they added.

These specific statements allow us to grasp the basis of the sisters’ decisions. They were founded on the commitment they made during their religious Profession, when they pronounced their solemn vows. It was a free and irrevocable commitment of their whole life in the Church that was expressed at that time, and abandoning it no longer depended on their own will or on that of others.

The National Assembly had proposed this declaration of intentions in the name of the principle of personal freedom and human rights. But the sisters did not consider that a decree from the National Assembly was enough for them to give up their life in the convent. They were, first of all, subject to the authority of their ecclesiastical superiors, to canonical laws, and above all to the judgment of God.

The position of Monsignor de Rohan, Archbishop of Cambrai, was very firm on this point. He wrote in March 1790 that “nothing can excuse the crime of apostasy of the sisters who have left the convent”. We have seen that the Community of Ursulines in Valenciennes was perfectly unanimous in their desire to be faithful to their religious vocation. The majority of the sisters’ communities made the same choice. However, some communities had their declarations for leaving the convent registered. They were generally very poor houses, and it is clear, from their declarations, that poverty led these communities to abandon their religious life, in order to enjoy at least the benefit of a pension.

The declaration of intentions and the inventories of goods that followed created severe internal tensions in some communities. The civil authorities sent a letter to the sisters of their Department reminding them of the obedience they owed to their Superiors. To this letter, the Ursulines replied; “We have never lost sight of the vow of obedience that we have made, and we hope that with the grace of God, we will be faithful to it until our last breath”. A moving testimony, when we know what they were going to endure!

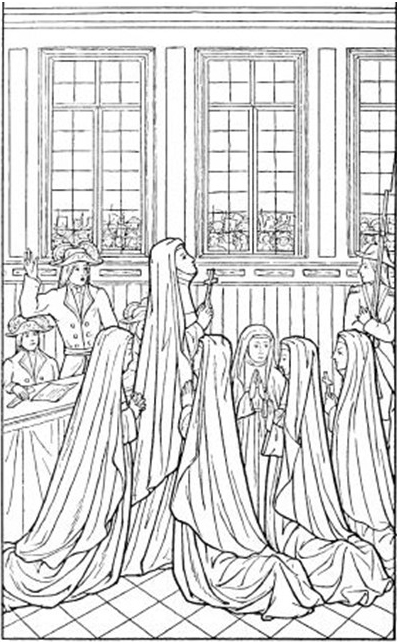

Wearing a religious habit was therefore prohibited. This decision encountered a deep resistance among the sisters. The habit, which they had received solemnly during the Clothing Ceremony had been the first act of commitment to the community. It had a great symbolical meaning, and recalled their Baptism and the meaning of a life for Christ, of getting rid of the old life and putting on the new one, who is Christ the Lord.

The Ursulines of Valenciennes never submitted themselves to this decree banning the wearing of a religious habit. When they arrived in Mons, they wore their religious habit “that they have never left”. At her trial, Mother Desjardins declared that “she never left the habit of the Order”. However, the sisters were to climb on to the scaffold without their forbidden religious dress.

The Revolutionary regime considered as very important the transgression of this prohibition. Wearing a religious dress was a reason for being arrested. This can be found on the lists in the prisons. It was certainly a motive for condemning the Ursulines tried in Douai.

The Revolutionary regime considered as very important the transgression of this prohibition. Wearing a religious dress was a reason for being arrested. This can be found on the lists in the prisons. It was certainly a motive for condemning the Ursulines tried in Douai.

Since ecclesiastical goods had been nationalized, the Ursulines were to undergo unending efforts to assess their confiscated property and buildings, in order to compute the amount of pension that could be allocated to them as a compensation.

The Civil Constitution established a Constitutional Clergy. Bishops and priests would now be elected. On November 27th, 1790, an oath of fidelity to the nation was demanded of all priests, without reference to their Christian faith. The Pope condemned this oath in 1791. The dioceses would henceforth be modelled on the newly created Departments.

Monsignor de Rohan, Archbishop of Cambrai, refused to pronounce this oath and was dismissed. He went into exile in Mons, in part of his diocese situated in the Austrian Netherlands. He was replaced by Claude François Primat. Bishop de Rohan strongly denounced this bishop as an “intruder” and recommended the faithful of his diocese to abstain from any relation with him. The Ursulines of Valenciennes remained loyal to Bishop de Rohan and obeyed him.

An oath was also demanded from the Ursuline teachers, considered as civil servants. It became compulsory in the Department of the North in December, 1791, but the municipality of Valenciennes did not seem to have asked the Ursulines to take this oath.

Because of their attachment to a rebellious clergy, the Ursulines were exposed to the hostility of the Revolutionaries, because of their refusal to allow a priest who had sworn the oath, to celebrate in their convent. They were fined 200 pounds for having violated the decree to close their chapel to the public. They were questioned about the presence of an unsworn and refractory priest in the convent. They were even denounced by a sworn priest as teaching their pupils principles opposite to the Constitution.

On October 1st, 1792, a new decree put a definite end to their life together, by deciding that from that date on, the houses occupied by religious had to be evacuated and put on sale as soon as possible. The community of Ursulines in Valenciennes then decided to ask for hospitality from their Sisters in Mons, with whom they were specially united. They had previously belonged to the same diocese of Cambrai, and published together their Directory, specifying the ways to apply the Constitutions that were common to them. In 1732, sisters from Valenciennes had participated in the foundation of Ursulines in Rome, by the Ursulines of Mons. It is therefore easy to understand that when life in the convent was abolished in France, the Ursulines of Valenciennes sought refuge among their sisters in Mons.

This choice had the great merit of allowing them to keep their life in common, a life that was becoming impossible in France, as the authorities no longer tolerated that sisters live together in the same house. Their decision implied perfect confidence in Providence and in the charity of their sisters in Mons. Leaving France, in fact, meant giving up all means of subsistence and the promised pension. The sisters thus showed that they were worthy daughters of Angela Merici who had said, “Hold for certain that God will not fail to provide for your bodily and spiritual needs, provided that you do not fail before God”.

The Ursulines left their convent in the middle of September. Mother Dominique Dewallers and Mother Cécile Perdry, who were too elderly to leave, remained in Valenciennes, each of them entrusted to a Lay sister, as well as Mother Marie-Thérèse Castillon. Asked by the judges when she left the community, Mother Clotilde replied that “she left when the community was suppressed, and that on the same day, they left with a passport from the city officials that allowed them to withdraw wherever they thought it would be good, even to Austria, and that she went to Mons”.

In fact, the archives of Valenciennes contain passports drawn up in the same terms and requiring the bearer to “freely pass, stay, and return”. It is moreover unthinkable that an entire community could have crossed the border without those documents. In this time of war, the border was severely guarded by the army.

The whole community of Valenciennes joined the house of Mons, as was related by Mother Honnorez, an Ursuline in Mons, author of a “Report on our community of Religious Ursulines In Mons, during the French Revolution, written by a Sister who was an eyewitness”: ”On September17th, at six o’clock in the evening, the first cart arrived. They said that the others, who had no other refuge, would arrive in half an hour. Our Mothers of that time could not refuse to give them hospitality. When they had all arrived, they went to the church, 26 of them, and all in their religious habits that they had never left, they sang there the Te Deum”.

It was with great kindness that the Ursulines of Mons welcomed their sisters from Valenciennes for they were going to find themselves very cramped for lack of room. They were “fed free of charge during fourteen months”, the Report said. Some took up teaching activities, six as assistants in the day classes, two others as teachers of writing and arithmetic to the boarders.

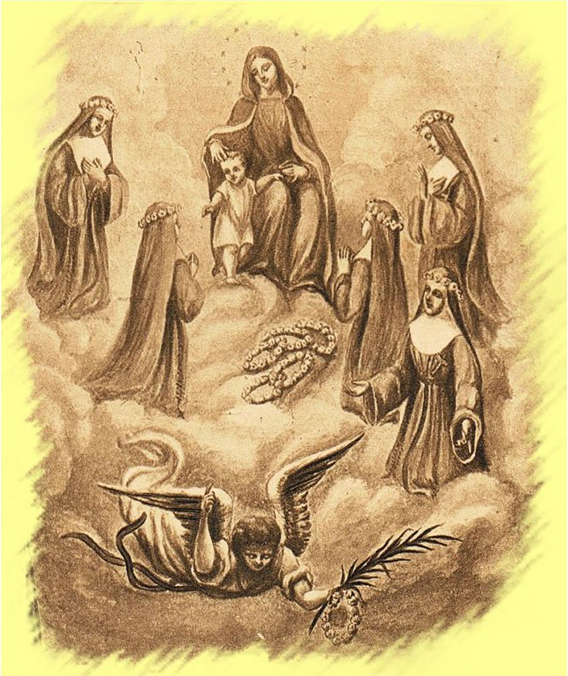

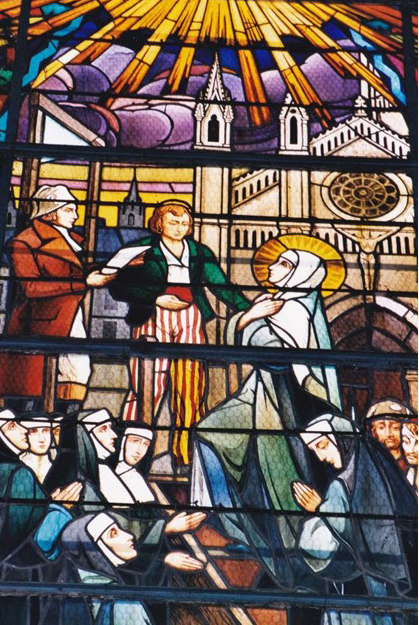

On October 28th, the Ursulines of Valenciennes enlisted in the “Confraternity to obtain a holy life and a happy death under the protection of Saint Ursula and the eleven thousand Virgins”. They dedicated themselves to Saint Ursula with this prayer “Saint Ursula, I take you as my patron saint and as my advocate at the time of my death, and I ask you to assist me especially in the last moment, on which my eternity depends”

We can see the essential importance given to the preparation of death, to the judgment of God that follows, on which eternal salvation depends, and to the role of intercessors. To die is to appear before God with all of one’s real life, and it is important to prepare it.

At the time of their death, the Ursulines were surrounded by their sisters who recited for them the Prayers of the Dying written in the Ritual of the Sisters of Saint Ursula “for the administration of the Sacraments of Confession, Communion, Extreme Unction, and visits to the sick”. The Ursulines imprisoned in Valenciennes recited them for the others, the day before their death.

By enlisting in the Confraternity, the Ursulines thus ensured the presence of intercessors and advocates in heaven. This devotion certainly played a big role in the preparation of their death. The Ursulines of Valenciennes, two years later were going to experience martyrdom like their patron saint.

The Revolution that the Valenciennes Ursulines had fled, came back. On November 6, 1792, the French General Dumouriez won the battle of Jemappes and entered Mons on the following day. The "country of Hainaut" was annexed and formed the 86th French Department as "Department of Jemappes" by a Decree on March 2, 1793. The Ursulines had then returned to the land of France.

The reception of the Ursulines of Valenciennes by their sisters in Mons was a temporary measure. The Ursulines of Valenciennes were approached by the Superior of the Ursulines of Liège to come and restore this house which played a great role in the spreading of the Order throughout Europe and which was then a mere shadow of its former self. The Ursulines of Valenciennes proposed to restore a boarding school and free classes there. This project did not succeed, because once again, the wind of history had taken another direction.

Following the Battle of Neerwinden on March 18, 1793, the Austrians recaptured their former territories. They came back to Mons on March 27, and Mother Honnorez wrote: "Our sisters of Valenciennes therefore conceived the hope of returning to their convent."

Half of the Northern Department was also annexed by the Austrians. Valenciennes capitulated after a siege of several weeks. The Austrians had the annexed French regions put under the authority of a provisional administration, known as the "Jointe de Valenciennes", which had, among its many responsibilities, that of deciding the reintegration of religious communities. Many priests from Valenciennes who had retired to Mons, then returned to their parish, recalled by their faithful. The Ursulines did the same.

Mother Leroux declared during her trial that the Ursuline community had returned to Valenciennes to obey the Archbishop's orders and to meet the insistent demands of the inhabitants of Valenciennes. Mother Therese Castillion, on behalf of the community, received through the “Jointe de Valenciennes” the authorization of resuming their religious life in their home. (This was not granted to the Brigittines). The Vicariate of Cambrai "knowing that the Ursulines of Valenciennes are on the point of returning to their house, appoints Father Leroy to preside over the election of a superior at the end of Mother Clotilde's mandate of 3 years and to receive the vows of Mother Lepoint, as soon as they return."

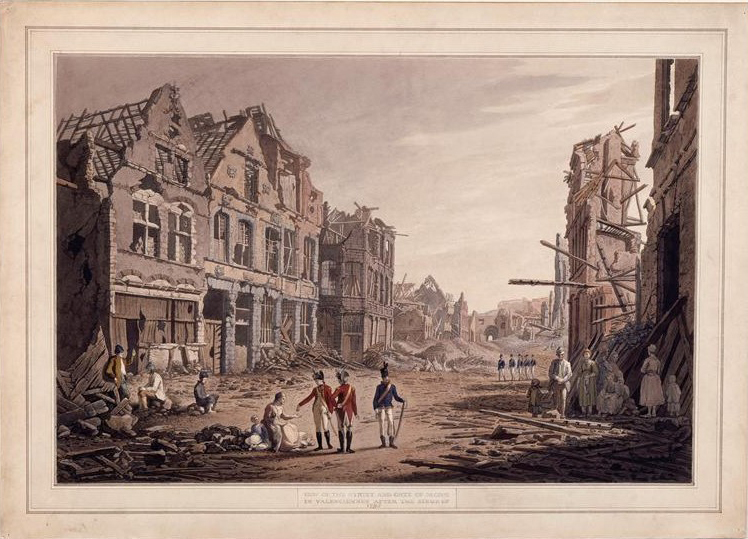

During the siege of Valenciennes, the Ursuline convent had been converted into barracks. After having the necessary repairs done, the community returned to their convent. "They were at the height of the joy of coming back home, everything was fine; a former novice made her profession at Easter. Then they welcomed new candidates and there was a religious Clothing."

On November 26, 1793, Mother Clotilde was re-elected for another term of three years, which would be tragically abbreviated. Moreover, the novice who had not been able to pronounce her vows because of the prohibition, Emerante Lepoint, in religion Mother Angelique, made her profession on April 23, 1794. She was to be the future restorer of the community. In 1816, she had her Profession of solemn vows proved by a document from a notary.

The community received three new members during this period. All three would be among the martyrs: Josephine Leroux, sister of Mother Scholastique. “a Poor Clare Urbaniste”, who left for Cambrai, when the communities were abolished. She returned to Valenciennes under Austrian occupation and chose the Ursuline habit, "wanting to resume her religious profession", she said. Two Brigittine nuns, Sister Marie Erraux and Sister Liévine Lacroix both from Pont-sur-Sambre, left for Mons, when they were banned, to enter the community of Sainte-Marie. Having learned that the community of the Ursulines in Valenciennes had been restored, they entered in that house.

A new change of political regime came about.

On June 26, 1794, the Austrians were defeated in Fleurus by the French troops of General Jourdan.

On June 1st, Mons capitulated. The four citadels of the North surrendered quickly this time.

The regions occupied by the Austrians came back definitely to the French territory.

In France, during the year 1793, the Revolutionary regime hardened strongly, and also showed a desire to un-Christianize the region. Sworn priests celebrated behind closed doors; the worship of Reason became established. A Republican ritual was designed to erase all traces of Catholicism: a Republican calendar, celebrations of “decades”, renaming of towns, streets, cemeteries... In some places, there were real religious persecutions.

As soon as the French arrived at the gates of Valenciennes, the Austrian Commander of the Square capitulated and began discussing his surrender with the enemy. Created in 1793, the People's Representatives in Mission were provided with exceptional powers: they had authority over all local administrations, military offensives and accountability only to Paris. They also put in prison the people accused of counter-revolutionary activities and they also set up exceptional courts with military commissions.

As the French troops approached, a large number of Valenciennes residents left the city to seek refuge in Austrian territory for fear of reprisals. The Ursulines had no instructions from their bishop. Bishop de Rohan went into exile in Nijmegen. Bishop Primat was dismissed in 1793. Father Parisis, their chaplain, also emigrated beyond the Rhine. Only Father Lallemand advised them: "My daughters, do you think you have enough strength not to falter in the face of death? It is better to flee persecution than to yield to apostasy. I will stay here because I am a shepherd and my sheep are in the mouth of the wolf. But you have only your souls to save."

This was not the advice they put into practice. After a discussion with her Council and with the community, Mother Clotilde decided the community's course of action by saying, "Because we promised God to stay in the convent until death, we will do so" and she added: "No resistance to external powers, but as long as we are not forced to leave, we are obliged to stay."

Arrested, imprisoned, tried...

The French came into the city on September 1st. The Representative of the People in Mission, Jean Baptiste Lacoste, expected to find a large number of emigrants in the city. He wrote: "This was a misunderstanding, there were no emigrants, but only a few priests who had avoided their arrest by leaving France and taking up their duties in the conquered country, and Ursuline nuns who had thought they could return to their former convent."

A Commission was set up to make arrests and put people in prison. "Seldom families did not deplore the arrest of one of their members. All clergymen and nuns were arrested, as were all those who had performed civil, judicial and military functions. Consequently, the prisons were full and St. John’s church, and that of St. Peter and of the Recollets were set up as branch prisons."

A Commissioner went to the Ursulines’ house and gave them the order to leave their convent within 24 hours. "When the French arrived and asked to leave their home within twenty-four hours, those who had relatives in the city left the house that day, but those who could not find any asylum for refuge, having still slept in the house, on awaking, were quite astonished to be arrested, as well as several others dispersed in the city."

The Ursulines’ first place of detention was their own convent, also converted into a prison, due to the number of prisoners. "They were put in prison in the classroom area where everything was sealed." They stayed there for several weeks.

On October 9th, Mother Clotilde was still imprisoned in the "House of the Ursulines" with the two Mothers Leroux, and the Sisters Erreaux and Barret. Mothers Vanot, Prin, Bourla, Ducret, and Desjardin remained jailed in the “Maison Saint Jean”. These were the two groups of religious sisters who were guillotined: those of the “Maison Saint Jean” martyred on October 17th; those in the house of the Ursulines, martyred on October 23rd. For the last days of their imprisonment, the Ursulines were brought together in the city prison by an order from the Military Commission.

Life in these overcrowded prisons was appalling. The report of the Committee informs us of the pitiful situation of the prisoners: "Prisoners lack bread, they are not given any daily distribution." "Straw is missing in the prisons" "All the prisoners demand bread and straw; many are lying on the ground”. The commission urgently appealed to the Directorate to supply straw, to enforce a Decree requiring the wealthiest prisoners to pay for the meals of the poorest and permit the prisoners to be fed by their relatives and friends. The Ursulines received the help of Elisabeth CLAIS, who helped Mother Angelique Lepoint escape; the latter restored the community.

However, the conditions of imprisonment remained deplorable, and serious epidemics of scabies, fever and dysentery were declared. Two health officers examined the prisoners and had some of them sent to places where they were healed. This was the case for some sisters in the community. Dr. Vandendriesche, a physician in Valenciennes, housed two Ursuline sisters, whom he later helped to escape.

The sisters told the Ursulines of Mons "how they were under arrest in churches, with an infinite number of priests and others, how they went to Confession standing, in full view of everybody."

A Popular Commission of 12 members was appointed by Lacoste to examine the reasons for the detention of all these suspects, and to establish new conditions: release for some and motives for putting others in prison after being judged. The public accuser of the Northern Criminal Court moaned that “his work is very incomplete and disrespectful”.

At the end of the trial, Mother Leroux wrote that they wanted them to give up their religion. “11 nuns, our future martyrs, have been accused of emigration”, a particularly serious charge. Others were brought before the Northern Criminal Court: Mother Marie-Therese Castillion, who had never left Valenciennes, Mother Felicity Messina, from Peruwe, and Sister Régis Lhoir from Mons, both from the Austrian Netherlands.

It was before a Military Commission that the sisters accused of emigration faced their trial. Military commissions, composed of five selected members of the army, were allowed to judge the rebels and the armed emigrants, and later, the priests accused of having left France.

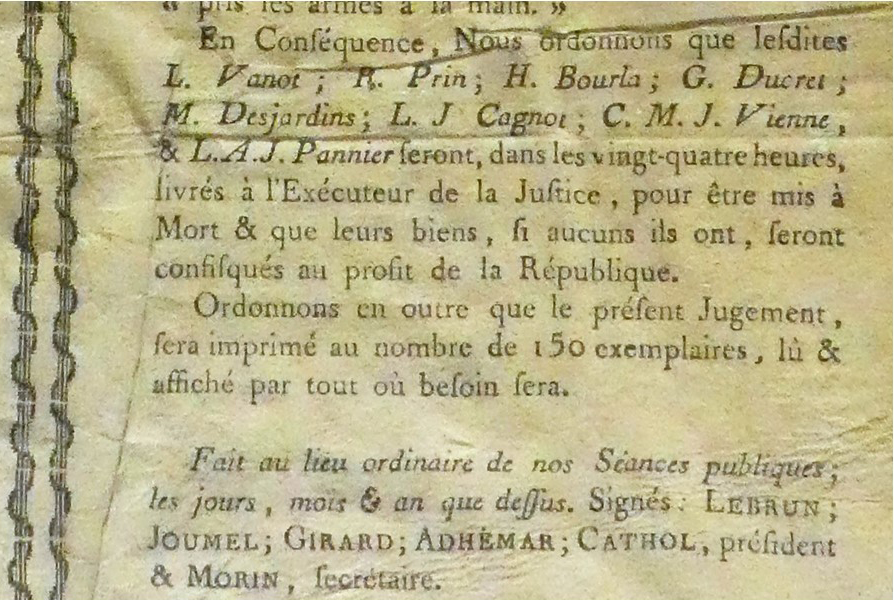

The Commissions were abolished because of misuse of power by some persons representing the people, but there were subsequent exemptions in the border area. The proceedings were conducted without any witness or jury. There was no appeal after the judgment was pronounced. Within 24 hours, a sentence of death had to be executed.

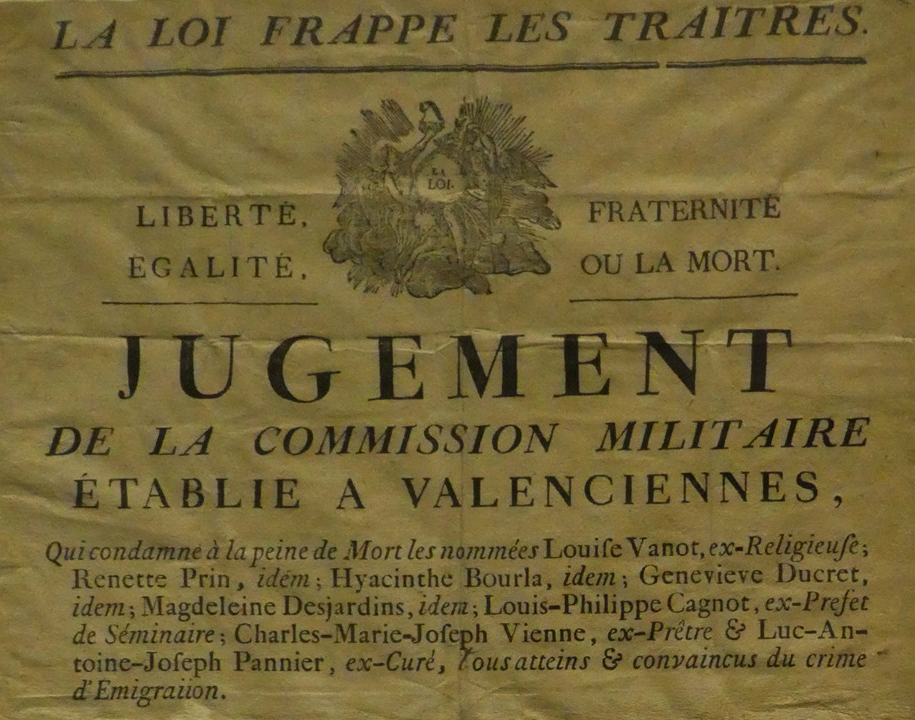

Jean-Baptiste Lacoste set up a military commission formed by General Drut and his staff to judge the emigrants taken up with arms in hands, as he wrote to the Convention. A list of individuals that he condemned were to be tried by the Commission. On “the 24 vendémiaire of year II” (the 24th of Oct. 1794), we find: "All emigrants who are designated by Article 74 of the Act of March 28, 1793, adding priests or other deportees and people returning to French territory and those who acted militarily against France," that is, 116 people, 34 priests or religious, 13 nuns, and 69 lay men.

We find there ten sisters from the community of the Ursulines of Valenciennes who were to be guillotined: "Louise VANOT, Rennette PRIN, Hyacinthe BOURLA, Geneviève DUCRET, Magdeleine DESJARDINS under the same declaration, with the words "ex-religious" and further : "Clotilde PAILLOT, Marguerite LEROUX, Josephine LEROUX, Marie ERRAUX, Liévine LACROIX" also with the words "ex-religious." Sister Cordule BARRE was not included in this list, but she also was brought before the military commission. Of this group of 116 people, all lay people, were not guillotined, as well as five priests and three nuns.

"Accused of emigration" the Ursulines from the first group were almost immediately brought before the military commission. The legislation in this area was particularly severe: "The National Convention enacts that all French emigrants are banished forever from the territory of the Republic and that those who, in defiance of this law, would return will be punished by death... “

The 4 historians specializing in the history of the Revolution, called to testify before the Diocesan Information Court on the accusation of emigration held against the Ursulines, declared this unfounded, with, arguments to support them.

Because of the law of “22 prairial year II” (June 10, 1794), the Ursulines had to do without a lawyer. This law removed any way of self-defense on the part of those who were accused. The Court could convict them without prior instruction, without defenders and without witnesses.

The Ursulines, however, seem to have received advice concerning their defense. Charles Verdavaine, the city’s prosecutor, wrote: "Several nuns were placed in my office pending the appearance at the military commission; I observed for them that they had means to defend themselves, that they had agreed to return to their community, when during the invasion of the enemy their superior had reminded them, that according to the rules of their order, they were still subject to Obedience."

Mother Clotilde herself indicated a firm course of action to her sisters about their emigration: "If we are asked about it, we must answer so as not to betray the truth, that we have been in Mons with a passport from the municipality and that we returned to Valenciennes to be able to serve the inhabitants, by educating their children" And later: "Say that if you had known that you would be incriminated for having returned to France, you would have stayed abroad. But if you are asked for something contrary to the submission due to our Holy Father the Pope or to your religious vows, resist”.

The first sisters of the community were brought before the military commission on October 16 and executed the next day. On October 22, it was the turn for Mother Clotilde and five of her sisters to appear. They endured their trial and execution on the next day. The questioning of the sisters lasted briefly and we can find identical questions in the files of priests and religious questioned by this Court. The questions concerned the time when they left the community and where they went, the swearing of the oath, the reasons for returning to France - a serious offence.

The sisters defended themselves with great firmness and followed the advice given to them fairly closely. Obviously, their choice of life away from the world, and therefore their ignorance of all the legislation in force, the absence of a lawyer, did not allow them to use all the legal arguments giving them an advantage.

All explained that they went to Mons "with a municipal passport," as several of them stated. Two reasons were expressed as motives for their return to Valenciennes: the insistent requests of the inhabitants and obedience to their Superiors.

Regarding the violation of the laws by returning to France, many stressed the fact that at that time Valenciennes was no longer part of France, and Mother Josephine Leroux stated that she never left Valenciennes except for a three-month stay in Cambrai.

Several sisters explained the religious basis of their behaviour. Mother Leroux said that "she wanted to find again her functions as a nun", Mother Erraux: "that she had no other motive than to return to her state and religion” (to be understood in the sense of "religious community" in the 18th century). Mother Clotilde concluded the questioning by stating that "in behaving as she did, she wanted only to save her religion and not be an apostate."

All had been sentenced to death for emigration and accomplishing under the protection of the enemy, activities that had previously been forbidden.

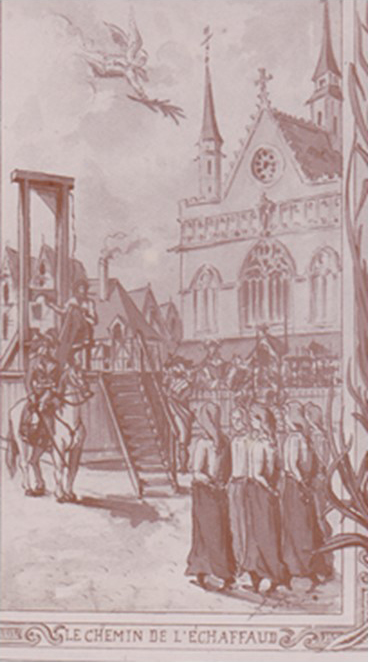

Climbing the Scaffold

As soon as they went back to the prison after having been questioned, the Ursulines who were to be executed on October 17th prepared for their death. They were:

- • Marie-Louise Vanot, 66, in religion Mother Marie-Nathalie, from Valenciennes

- • Hyacinthe Bourla, 48, in religion, Mother Marie-Ursule, from Condé

- • Marie-Madeleine Dejardin, 34, in religion, Mother Marie-Augustine, from Cambrai

- • Marie-Geneviève Ducrez, 38, in religion Mother Marie-Louise, from Condé

- • Jeanne-Queen Prin, 47, in religion Mother Marie-Laurentine, from Valenciennes

"Mother Clotilde then did nothing more than help those who were going to die, to appear before God."

"All of them knelt down, placing a small crucifix in the middle of them. Mother Nathalie began to recite the Prayers of the Dying; the other nuns also began to pray God for them.”

All night long, they recited together the Prayers of the Dying and the Office of the Dead. In these Prayers for the Dying, taken up in their Ritual, the Ursulines read the Passion according to St. John, said the Litany of the Virgin and especially the 7 penitential psalms (Ps. 6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, 143) including the Miserere and the De Profundis that had an important place.

At the time of their farewell, they asked for forgiveness from their sisters, thanked the Superior and requested her last blessing.

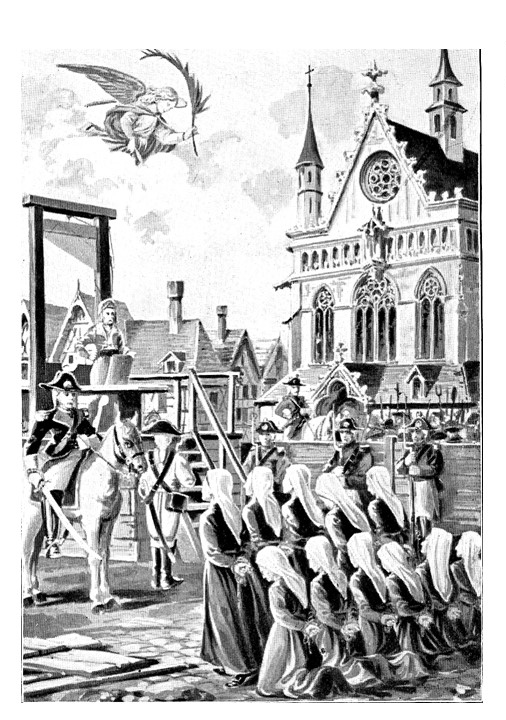

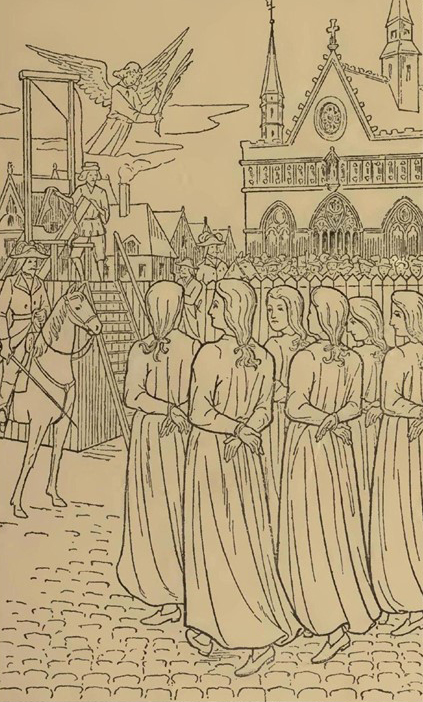

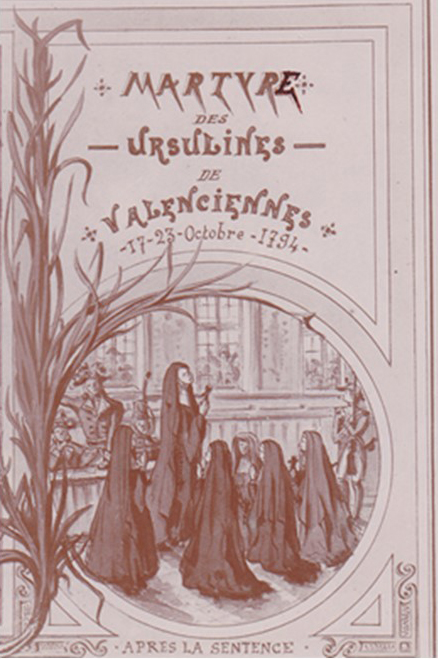

The execution of the Ursulines was a fervent and vivid remembrance in the memory of those who witnessed it. There were many statements on this subject in the canonical trial, and all these testimonies express together what struck all the witnesses of the execution: the joy and courage with which the Ursulines went to death singing, and the fact that they were stripped of their religious habit.

However, the climate of anxiety that had arisen from the setting up of the guillotine in the Place d'Armes became even more intense when it was found out that these women were religious sisters, their former teachers for some, who were going to the scaffold.

"We scarcely dared to talk and look, for fear of being worried;" said a witness.

It was with sadness and dismay that the inhabitants of Valenciennes saw the sisters leaving the prison, "their hands tied behind their backs, in petticoats and shirts, with headbands on their heads."

But the attitude of the victims themselves contrasted entirely with a general atmosphere of despondency.

Terms of joy and courage come up in all the testimonies characterizing their ultimate attitudes. And what deeply affected the audience included the fact that the sisters sang the Litany of the Blessed Virgin and the Miserere. At the foot of the scaffold, they sang the Te Deum.

Mother Nathalie Vanot was called first and climbed the steps of the scaffold firmly. Mother Laurentine and Mother Augustine, as well as Mother Marie-Louise and Mother Marie Ursule were the four other Ursulines to be guillotined on that day.

And one witness said, "As long as there were two nuns left, they sang the hymn of martyrdom. All we could hear was their voices and their singing; the rest was in dead silence. A cry, a complaint: it was the scaffold.”

In her farewell letters, Mother Clotilde wrote with maternal pride: "They went to death as if it were a very great triumph. They flew to their torments with a joy and a courage that filled the executioners with admiration.”

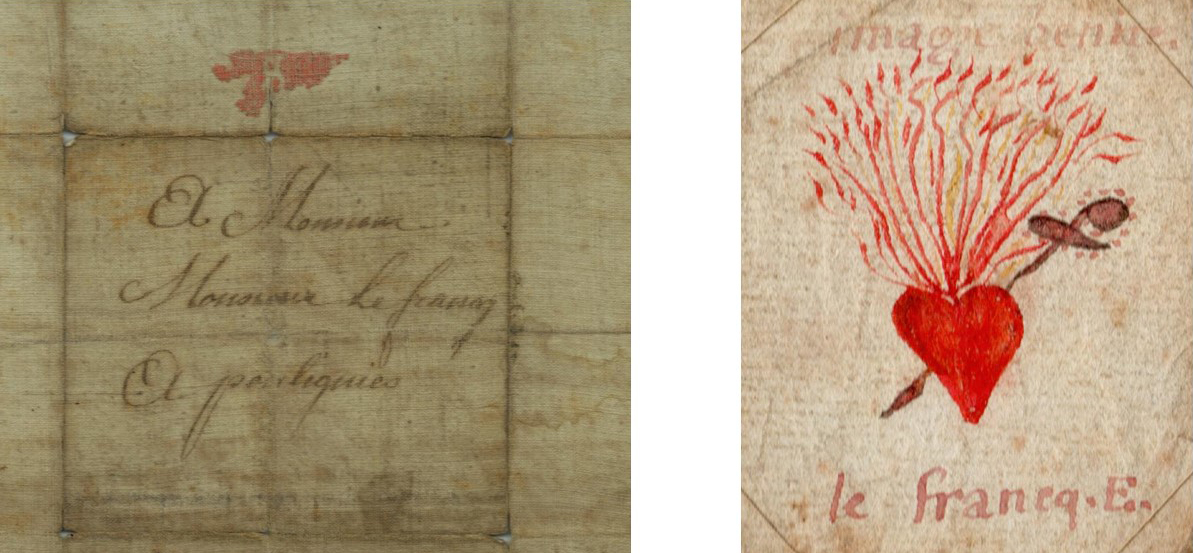

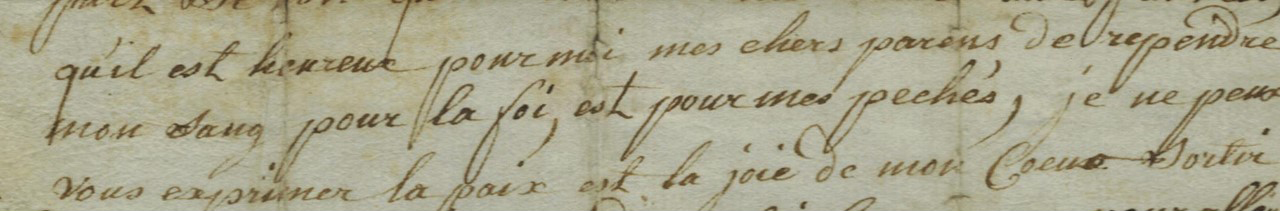

The Ursulines still in prison knew that they too would soon be guillotined. They took advantage of this brief respite to write farewell letters, five of which have reached us: a letter from Mother Erraux to her brother, two from Mother Scholastique Leroux to sisters from Mons and two from Mother Clotilde.

They express their desire for martyrdom, so as to be identified with Christ up to the end, in his passion and in his death.

Mother Scholastic wrote: "Daughters of St. Ursula, we shall give our lives as she did, for His love (for the love of the Lord), and in love, give Him back death for death.”

In front of such generosity, the Lord responded by filling them with his grace. They found themselves full of the strength and joy of the Holy Spirit: "I cannot express to you the peace and joy in my heart," Mother Erraux wrote to her family.

"I am the happiest person in the world," wrote Mother Clotilde.

On October 22nd, the Ursulines in prison were questioned. These include :

- • Clotilde-Joseph Paillot, 55, in religion Mother Clotilde Angèle Joseph de Saint Borgia, from Bavay

- • Anne-Joseph Leroux, 47, in religion Mother Anne-Joseph, from Cambrai,

- • Marie-Marguerite Leroux, 45, in religion Mother Marie Scholastique, from Cambrai,

- • Jeanne-Louise Barré, 44, in religion Mother Marie-Cordule, from Sailly-en-Ostrevent,

- • Marie-Augustine Erraux, 32, in religion Mother Anne-Marie, from Pont-sur-Sambre,

- • Marie-Liévine Lacroix, 41, in religion Mother Françoise, from Pont-sur Sambre,

Questioned on the 22nd of October, they were tried and sentenced on the 23rd and executed on the same day.

Eleven Ursulines climbed the scaffold, and soon after their death, they were compared to the eleven thousand virgins accompanying Saint Ursula to martyrdom.

They, too, spent their last night in prayer. They gathered for “the Last Supper", like the one the Lord celebrated on the day before his death. They were happy to think that on the next day they would be in heaven. And they had the happiness of being able to receive Holy Communion for the last time, thanks to a priest imprisoned with them.

During this Octave of the feast of Saint Ursula, they had a particular confidence in their patron saint. They left for the scaffold with four priests who were also to be guillotined. Mother Scholastique said: “We forgive our judges, our enemies, and our executioner”.

Sister Marie-Cordule Barré had been forgotten in prison. After the others left, she begged to be able to share the fate of her sisters. She was answered: they came back to look for her, tied her hands behind her back, and she joined her sisters. “My life, no one takes it, but I give it”, Jesus said in the Gospel according to Saint John. Following His footsteps, the martyred Ursulines transformed their cruel death into a total gift of pure love.

Along the way, they sang the penitential Psalms and the Litany of the Blessed Virgin. Mother Clotilde thanked the soldiers of the escort: “We are so grateful to you, because this is the most beautiful day of our life. We pray God to open your eyes”.

The two sisters, Mother Scholastique Leroux and Mother Anne-Joseph Leroux, who had made profession on the same day, were offering the sacrifice of their life together. The two Brigittines from Pont-sur-Sambre, Mother Françoise Lacroix and Moher Anne-Marie Erraux who accompanied them, were also together for their martyrdom. Sister Cordule gave her life as her patron saint did. She was united to her sisters in martyrdom, according to her desire.

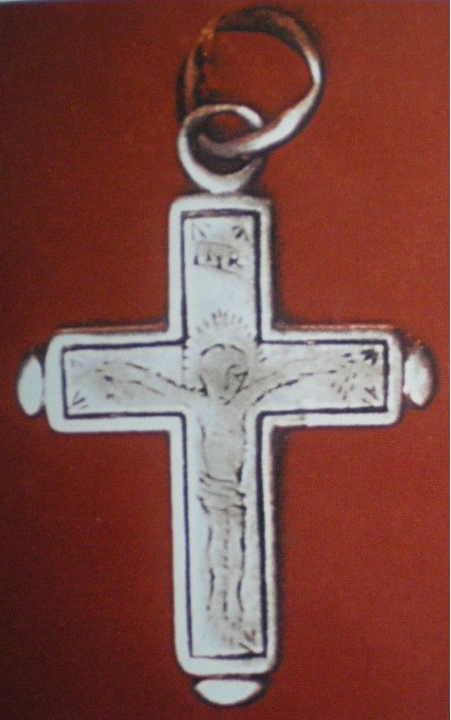

Mother Clotilde wanted to be executed last, in order to encourage up to the end, those who had been entrusted to her. The executioner snatched off the little cross she was wearing around her neck.

When they arrived at the scaffold, they sang the Magnificat, expressing so well the song within their hearts: “My soul exalts the Lord, my Spirit exults in God my Saviour”. The Magnificat rose high in the sky, and then gradually weakened according to the rhythm of the executions.

October 23rd was the anniversary of the solemn profession of Mother Clotilde. Thirty years earlier, she had entrusted herself to God through the total gift of herself. On this anniversary, she was ratifying the consecration of her youth. Her faithfulness was never interrupted, never denied. The supreme sacrifice of her life occurred during her martyrdom. She had yearned for it with such deep desire and spiritual joy! On this blessed day, she made her own the prayer found in the Ceremonial:

“My God; I now ratify with all my heart the gift I made to you of myself by the vows I pronounced during my Profession. Receive me as a sacrifice through the death I am expecting from you, as the fulfillment of my vows”.

An eye-witness reported; “I still see her on her knees in the scaffold. She was the last one, I think. I still hear this intrepid woman encouraging her Sisters and singing with them the praises of God, until the moment when nothing was heard in the whole city, except a silence of dismay”.

And the Ritual said: “Let the troop of Angels of light come to receive your soul, as it leaves your body. May Jesus show you His face of kindness and joy, and place you among those who are always in His company”.