Looking back. Short stories from the Archives

27/09/2023

World War II - Jews hiding in religious institutes in Rome

Interview for the ORF

In September 2023, the Generalate had the pleasure of participating in an interview for the Austrian radio and television station ORF for a report entitled 'World War II - Jews Hidden in Religious Institutes in Rome'.

Sister Mariangela Mayer, Local Prioress of the Generalate, and Emanuela Lauro PhD, General Archivist of the Archives of the Generalate (AGUUR), participated in the interview.

It was a reason of pride for the Institute to have been able to witness the important role played by the community of the Generalate of the Ursulines of the Roman Union in Rome in welcoming Jewish refugees (and others) during such a dark period in history.

|

|

|

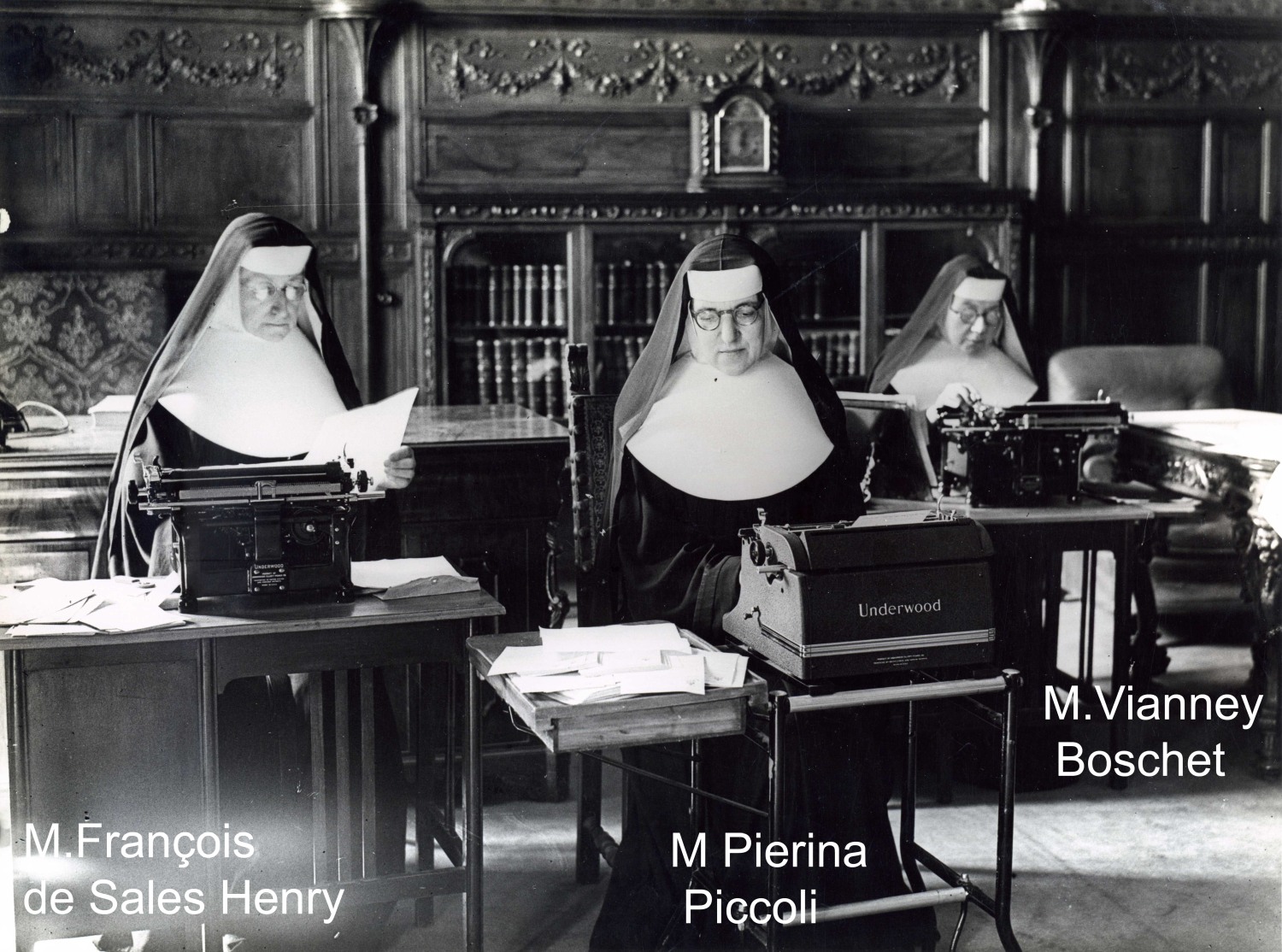

During the war years, Jewish families - or individuals - sought help from religious houses by direct connection, or through lists of convents delivered by bishops to Jewish welfare committees. Religious houses seemed potentially safe because of their connection to the Holy See; already in 1940, immediately after Italy's entry into the war, the Apostolic Nuncio to Italy, Monsignor Borgongini Duca, had been instructed by the Secretariat of State to make contact with religious institutes that included foreign members - from enemy countries - to give instructions to protect both persons and property. This operation was carried out with the collaboration of three Ursulines of the Roman Union, who served at the Nunciature of Italy, located a short distance from the Generalate on Via Nomentana, throughout the war period, in June 1940. [1] The three Ursulines are Mother Marie Vianney Boschet (French), employed at 'Office Affairs', Mother Marie François de Sales Henry (American), at 'Information' and Mother Maria Pierina Piccoli (Italian), assistant general, at the 'Prisoners of War' Office [2] (fig. 1). Besides them, other Ursulines also worked at the Nunciature: Mother Marie Patrick O'Riordan from Ireland (fig. 2) and Mother Marie Stanislaus Polotynska from Poland (fig. 3).

During these years, the general government, led by Mother Marie de Saint Jean Martin, was in exile in the United States; a few assistants and sisters who were part of the Community remained in Rome. The Generalate community opened up to hospitality as early as 1940, especially to wanted Poles. Life in the city and within the walls of the Generalate was anything but easy. At the end of 1941, the house was under surveillance: on 28 November, a man showed up to make adjustments to the telephone line; after he left, the sisters discovered a new line fixed along the corridor, which meant that the Gestapo was able to intercept not only telephone communications, but also to listen in on conversations inside the house.

As time went by, life for the community - and its guests - became more and more complicated: food was scarce, electricity and gas rationing made it even more difficult to provide meals and everything else, even water was in short supply. The large garden was a blessing, allowing the cultivation of vegetables and greens, and the presence of some farmyard animals such as chickens, rabbits, pigs and a cow. Because of the repeated thefts, chickens, chicks and rabbits were taken to the fourth floor for the night, while the pigs found shelter in the laundry room. Another worry was caused by the large windows that allowed the moonlight to penetrate and mislead the eye: the fear was that the police would believe that the house did not respect the curfew [3]; the windows were in fact covered with blackout paper.

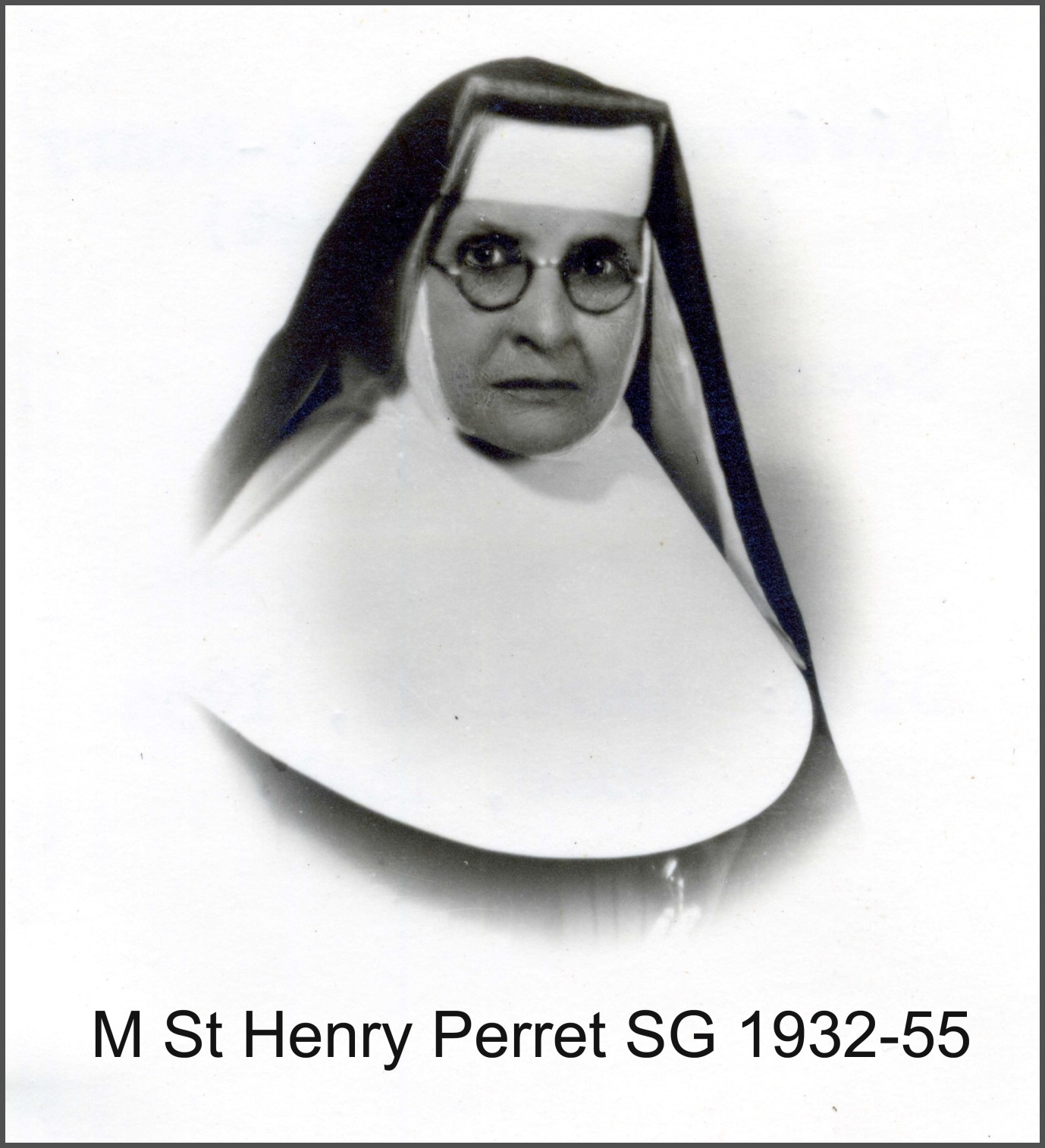

After the occupation of Rome in September 1943, many Jews knocked on the doors of the Generalate, but initially the sisters hesitated because the internationality (particularly of M. Magdalen Bellasis (fig. 5), Prioress of the house, English and M. Saint Henry Perret (fig. 6), Assistant General, American) put them more at risk, and susceptible to police control, despite the Declaration of the Governor of the Vatican City State that the institute was 'under the authority of the Sacred Congregation of Religious [...] and as such not [...] liable to search or requisition'. This hesitation was short-lived and the sisters soon took in many people. The guests - who were given documents with false names - were divided into two groups: the girls and children were housed in the house as boarders and lodgers; a second group consisted of 'gardeners', 'night watchmen' and 'doormen', housed in a building bordering Via Nomentana called 'Casa di Foschia' (no longer in existence). In the event of a search, the girls and women would appear to be religious, while the children were taken to the Ursuline school in Via Nomentana 34. [4] The property of the Generalate was under the protection of the Vatican, but when the Germans took over from the Fascists in September 1943 - and the persecution of the Jews became more serious - some convents and seminaries were rounded up by the Germans. The Villino was occupied by the Wehrmacht who set up offices there, but the convent was fortunately spared.

|

|

|

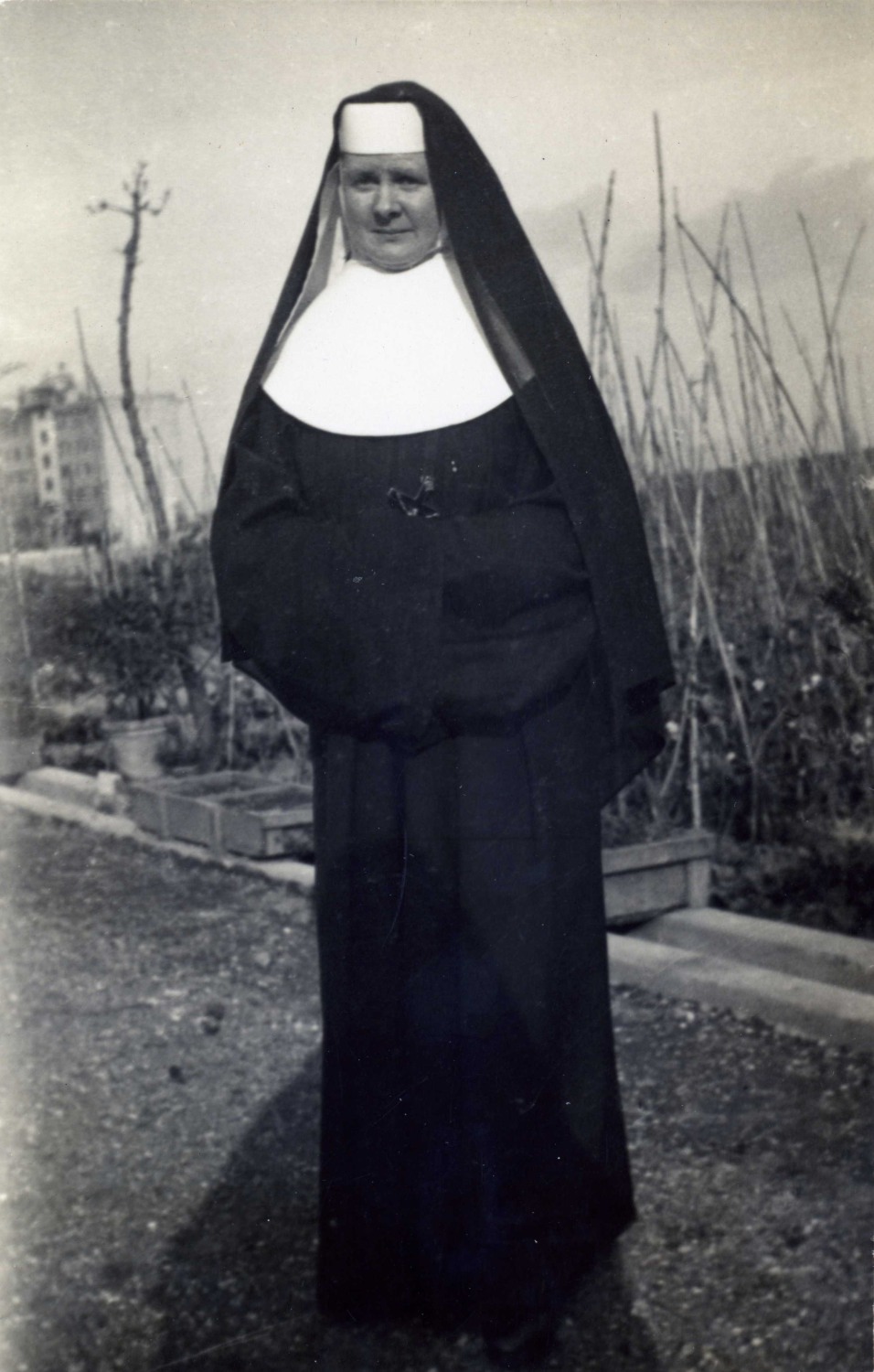

| 5. Mother Magdalen Bellasis (AGUUR ©). | 6. Mother Saint Henry Perret (AGUUR ©). | 7. Mother Marie Xavier Marteau (AGUUR ©). |

Thanks to the list compiled by historian Renzo De Felice, we know that the Ursulines of the Roman Union housed around 103 Jews. [5] Just in the last few days, it has been announced that unpublished documentation has been found in the archives of the Pontifical Biblical Institute, with a list of those (mainly of the Jewish religion) who were protected in Rome from persecution thanks to the Church institutions that offered them refuge. [6]

Documents that could be compromising were avoided in the archives, as there are many gaps in the documentation relating to the war years. The courage and faith of the Ursulines meant that important documents were kept in the Generalate Archives, thanks to which the history of those years could be reconstructed. These are two diaries: [7]

- The Diary of Mother Magdalen Bellasis written between June 1940 and September 1944, with some gaps. [8]

- The Diary of Mother Marie Vianney Boschet written between 1940 and 1944. Mother took notes from day to day, which were then copied into a large register. The copyist stopped working in June 1942, but fortunately the handwritten diaries from 1942 to 1944 have been preserved. [9]

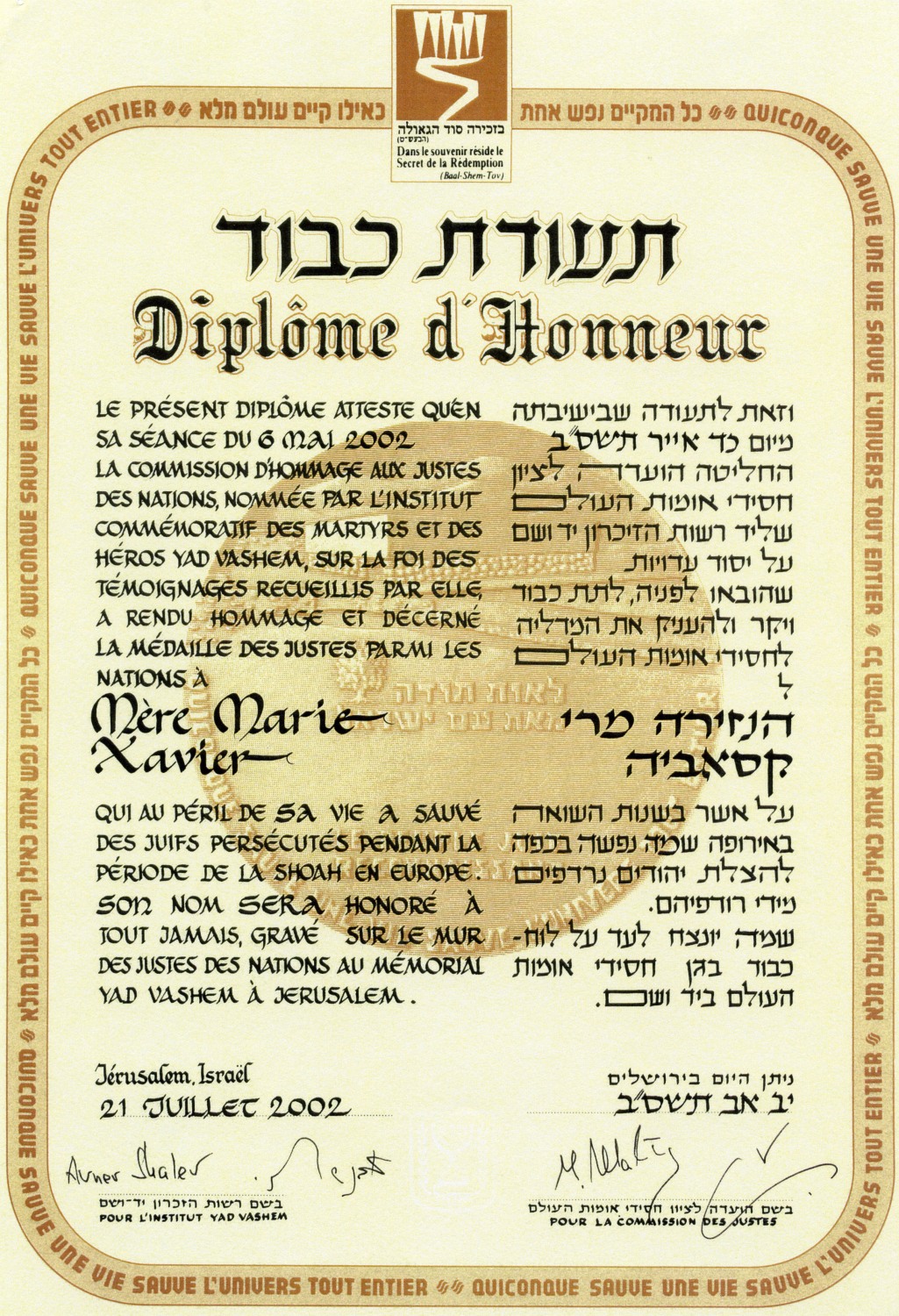

Both diaries document the daily challenges of war: from bombings to raids by garden thieves, from the absence of food and supplies to the sounds of raids, from telephone tapping to numerous requests for shelter. In both we can read some names of people who were rescued and hidden at the Generalate; among them are the Croatian sisters Lucia and Gisella Endelli, that is, Jetta and Gisella Hendel (Gisella was one of the youngest boarders, she was then only 8 years old); [10] and Maria Fornari, that is, Maria Luisa Della Seta (and a dozen family members). The latter was the creator of the title 'Righteous Among the Nations' awarded to Mother Marie Xavier Marteau (fig. 7) in 2002, [11] with a solemn ceremony that took place at the Generalate with the presentation of the 'Medal of the Righteous' (fig. 8), the 'Diploma of Honour' (fig. 9) and the gift of the olive tree from the Jerusalem hills, accompanied by a commemorative plaque and planted in the garden of the house (fig. 10).

The title 'Righteous Among the Nations' was created by the Israeli parliament in 1953, to remember and celebrate those who saved the lives of one, or more, Jews destined for the death camps by risking their own lives. It is the highest award given to non-Jewish citizens. In the Jerusalem boulevard leading to Yad Vashem, the Holocaust memorial, the names of the 'Righteous' are listed on the 'wall of honour'; a tree has also been planted for each of them. The Jewish survivor prepares the case, collects documents and testimonies and demands recognition for those who saved his life.

This is what Maria Luisa Della Seta did for Mother Marteau. Maria Luisa and her sister Marcella, in particular, are grateful to Marie Xavier Marteau for rescuing them and their family from the Holocaust, for being their guardian angel, for welcoming them and supporting them at all hours of the day and night, for giving them the courage to fight and go on with their own lives and that of their family, for the words of faith and hope always accompanied by a smile on her face. Mother Marie Xavier arrived in Rome in 1924, called by Mother Marie de Saint Jean Martin, then Assistant General, to be her secretary, a role she continued to hold even after Mother Martin's appointment as Prioress General. She remained in Rome during the war years, facing with faith and devotion the hard trials to which she was subjected. The honour conferred on her extends to all the sisters of the Generalate Community who, with great courage and confidence, each according to their role and function, welcomed persecuted Jews, giving them a safe refuge and a message of faith and hope.

By Emanuela Lauro Ph.D., General Archivist

________________________________

[1] Cf. G. LOPARCO, Gli ebrei negli istituti religiosi a Roma (1943-1944) dall’arrivo alla partenza, in “Rivista della Storia della Chiesa in Italia”, vol. 58 n. 1, gennaio-giugno 2004, Vita e Pensiero – Pubblicazioni dell’Università Cattolica del Sacro Cuore, pg. 115.

[2] Cf. L. MARIANI, Orsoline dell’Unione Romana, in DIP, VI, coll. 914-917.

[3] Cf. Speech of Mother Colette Lignon Prioress General of the Ursuline of the Roman Union, for the presentation of the Medal of the Righteous to Mother Marie Xavier Marteau, in “Inter Ursulines Bulletin”, special edition, December 2002, passim.

[4] Cf. L. MARIANI, Orsoline dell’Unione Romana, in DIP, VI, coll. 914-917.

[5] Cf. R. DE FELICE, Storia degli ebrei italiani sotto il fascismo, Giulio Einaudi editore, Torino 1963.

[6] Cf. https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2023-09/douments-pontifical-biblical-commission-nazi-persecution-church.html

[7] In addition to these diaries, some letters and photographs relating to the years in question are also preserved.

[8] Cf. AGUUR, Ge 02a, Diarium Guerre, Diarium 1940-1944 écrit par M. Magdalen Bellasis.

[9] Cf. AGUUR, Ge 02a, Diarium Guerre, Diarium de guerre de M. M. Vianney Boschet 1940-1944.

[10] Jetta's touching story was told by Martha Counihan, OSU, associate professor and archivist/special collections librarian at the Ursuline-founded College of New Rochelle, New York, in her book Jetta's story, Columbia SC 2017.

[11] For more on this topic see Speech of Mother Colette Lignon..., cit., 2002.