Maria Clementina Sobieska's stay at the Ursuline Monastery in Via Vittoria

06/06/2025

Maria Clementina Sobieska (Oława 17 July 1701 [1] - Rome 18 January 1735), betrothed to James, son of the deposed King James II of England, on her way to Italy to meet her fiancé was imprisoned by King George I of Great Britain - who feared that the male heir born of this union might try to return to the throne - with the complicity of the Austrian Emperor Charles VI. After about six months spent in Innsbruck, Irish officers in the service of James abducted the princess and set off for Rome with a first stop in Bologna, where, on 9 May 1719,[2] the wedding ceremony[3] took place by proxy; her fiancé was then in Spain engaged in some consultations in an attempt to regain the throne taken from his father. On 9 May, Clementina left for Rome where she was expected by the Pope;[4] she arrived in the eternal city on 15 May [5] and remained there until her death under the protection of Clement XI and his successors.[6] The wedding ceremony was repeated, with the participation of James, on 1 September 1719 in Montefiascone.[7] Clementina spent the four months before the wedding in Montefiascone, Rome, at the Ursuline sisters' monastery in Via Vittoria [8] (fig. 1).

1. Convent of the Ursulines via Vittoria Rome,

Generalate of the Ursuline Sisters of the Roman Union, oil on canvas (35.5x52.5 cm), 1860.

The foundation of the Roman monastery in 1688 was due to the persecution of Catholics in England. Maria d'Este, the wife of James II, King of England, had taken refuge in Brussels in 1679 together with her mother Laura Martinozzi,[9] Duchess of Modena. The two women had found a home near the Ursuline convent with whom they had established excellent relations during their stay in Flanders, so much so that they desired and requested the foundation of a convent in Italy. Having obtained the Pope's approval, six Ursulines from Brussels-Mons left on 9 September 1684 under the leadership of Mother Marie-Agnes de la Hamaïde and in the company of Her Serene Highness. [10] On their way to Rome they stopped at the Ursulines in Cologne and Dijon, and arrived at their destination two months after their departure. As soon as they arrived in Rome, being cloistered, they withdrew to the monastery of St Catherine of Siena in Magnanapoli to wait for a seat, but they had to wait a long time; only in 1688, in fact, did they receive a Brief from Innocent XI [11] granting them the privilege of enclosure and the authorisation to expand the institute throughout Italy. Laura died the year before, leaving a bequest for the construction of the monastery. Her daughter Maria Beatrice, Queen of England, enforced her mother's legacy and on 28 April 1688 the sisters moved into the new convent. [12]

On 7 May 1719, Monsignor Cervini, on the orders of the Pope, together with Monsignors Gualtieri and De Giudici went to the monastery in Via Vittoria to choose six rooms that would be adequate to accommodate a guest of such stature. [13] For the fitting out of the rooms, Clement XI had commissioned Monsignor Bartolomeo Massei, master of the chamber, and the foriere maggiore Don Girolamo Colonna Sciarra, trusted and ceremonial [14] people, who made Maria Clementina's new residence worthy of royalty, all at the expense of the Apostolic Chamber. The first record of the balances and justifications owed to various master builders and craftsmen who worked on the monastery rooms dates back to June 1719, but as the documents reveal, work had begun in May of that year, [15] shortly before the arrival of the new bride. Maria Clementina made her triumphal entry into Rome in May, an entry remembered and described as highly anticipated, and well received by both the upper echelons and the so-called Roman common people:

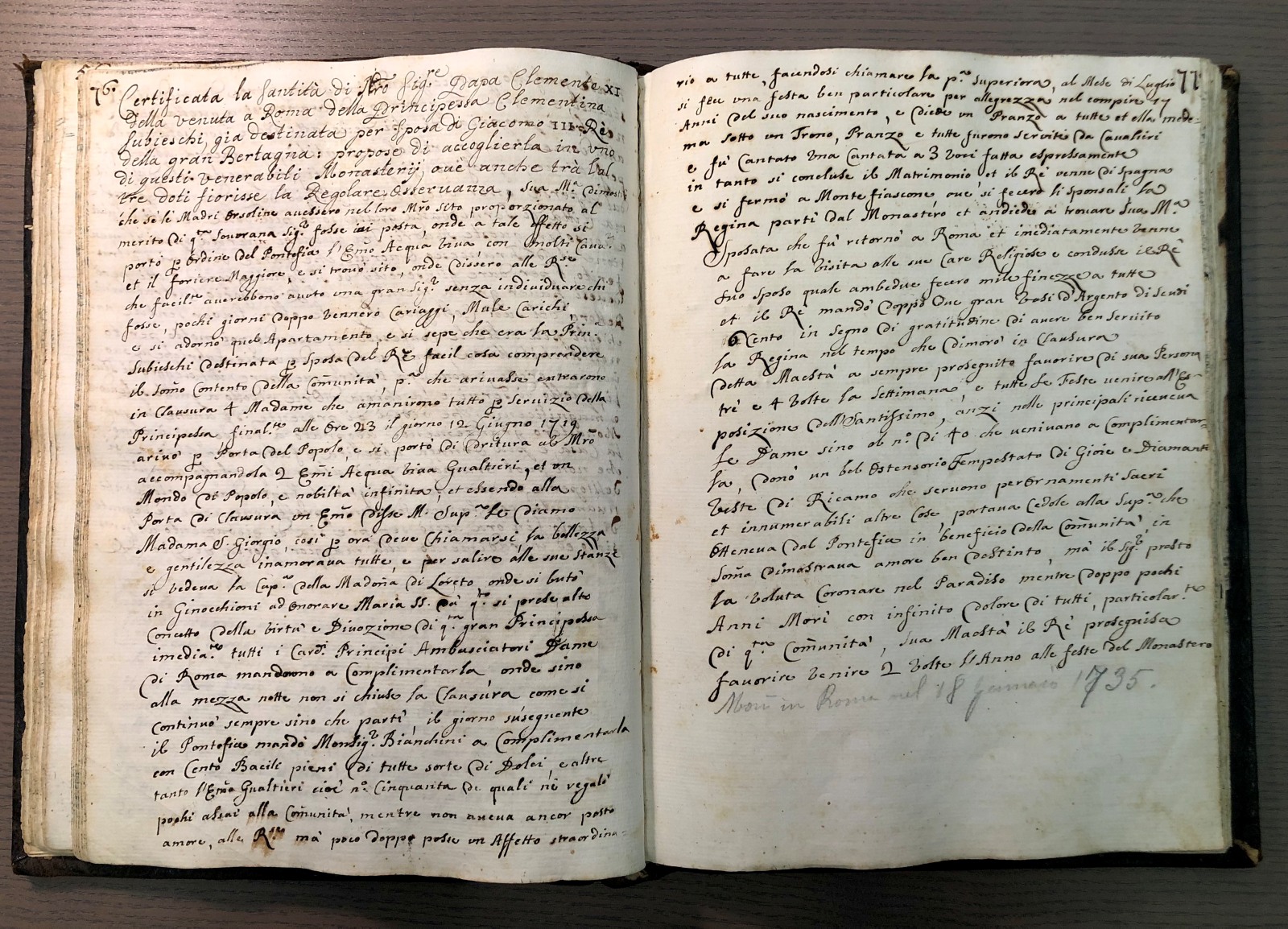

‘Immediately all the Cardinals, Princes, Ambassadors, Dames and Ladies of Rome sent to congratulate her, so that the enclosure was not closed until midnight, as it continued to be until she left. On the following day, the Pontiff sent Monsignor Bianchini to congratulate her with one hundred basins full of all kinds of sweets, and the most Eminent Gualtieri, that is, fifty, of which he gave a few to the Community’. [16]

More detailed is the testimony of the Chracas, which describes in detail the nature of the gifts and their presentation:

‘sent His Beatitude very soon on the following morning of Tuesday [16 May] his Promaestro di Camera Monsignor Bartolomeo Maffei to congratulate her on his behalf; Shortly afterwards, the Master of the House sent her a noble and sumptuous gift consisting of 52 courses of citrus fruits, sweets and other edibles of various kinds, admirably arranged in many rich basins decorated above and around with vague flowers and fettuccie, with various other cases of wine, and a tender calf, all painted white and red and garlanded with fresh flowers and adorned with ribbons. On the same day, the Most Eminent Lord Cardinal Filippo Gualtieri, Protector of the Kingdom of England, sent her thirty-eight other very noble guests, who also made a very fine appearance. In the meantime, the Most Eminent Lord Cardinal Astalli, Dean of the Sacred College, and, following his example, all the other Most Eminent Members of this Court, each sent his Master of the Chamber to congratulate the aforesaid Royal Princess on her journey and happy arrival, congratulating her in the name of their Eminences under the title of Madame of Saint George’. [17]

Maria Clementina thus found accommodation in the six rooms of the Ursuline Monastery intended for her. As mentioned, the new residence had been adequately prepared at the Pontiff's behest according to ceremonial etiquette. Unfortunately, a description of the rooms has not come down to us, but thanks to the payment notes of the Apostolic Chamber we can imagine the majesty and care with which the apartment was fitted out. Residence in a cloistered convent for a devout young woman [18] might have meant a life far removed from Roman worldliness, but this was not the case for Maria Clementina, who fulfilled all the ceremonial requirements while also allowing herself moments of leisure. On 21 June, the birthday of her consort James III was celebrated in the Ursuline monastery. [19] Also in the convent of Via Vittoria, on Monday 17 July, the birthday of ‘Clementina Sobieski Queen of England’ [20] was celebrated, ‘a luncheon was given to all under a throne, and all were served by knights and a cantata [21] for 3 voices written for the occasion was sung’. [22] On 30 August Maria Clementina went to the Pope's audience passing through the garden of the Quirinal; [23] ‘At 9 o'clock on Friday morning [1 September] this Queen of England left for Montefiascone to find King James her husband there’. [24]

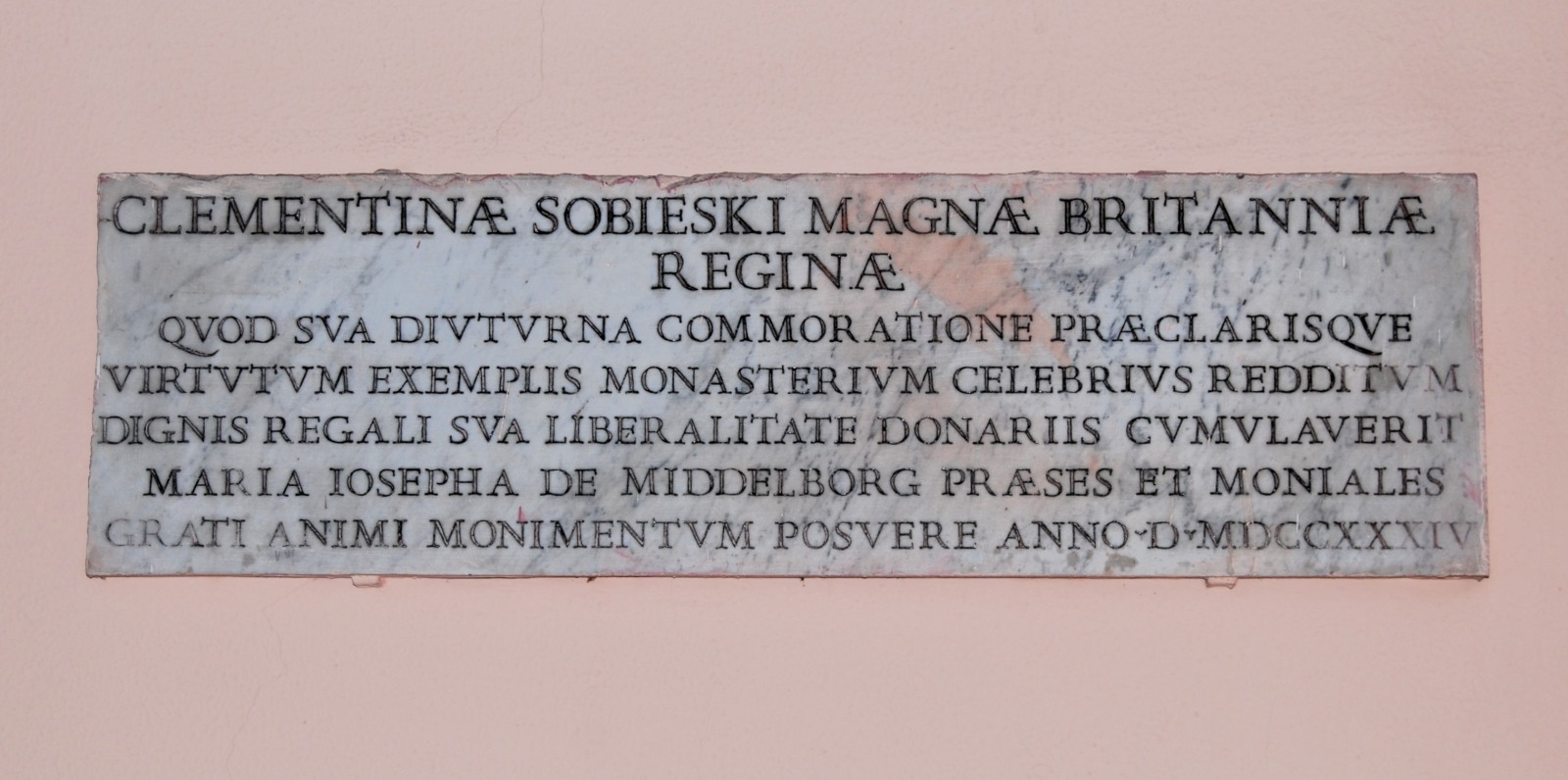

The marriage in Montefiascone ended Sobieska's stay with the Ursulines, to whom Maria Clementina always remained attached: ‘When she was married she returned to Rome and immediately came to visit her dear Religious and brought her husband the King, both of whom did a thousand delicacies for all of them and the King sent afterwards two large silver vases of six hundred scudi as a sign of gratitude for having served the Queen well during the time that she remained in seclusion, said Majesty always continued to favour her in person three and four times a week, and every feast day to come to the Exposition of the Most Holy Sacrament, indeed on the principal feasts she received the ladies up to the number of 40 who came to congratulate her, she donated a beautiful monstrance studded with jewels and diamonds, embroidered garments which serve as sacred ornaments and innumerable other things, she brought coupons to the Superior which she obtained from the Pontiff for the benefit of the Community, in sum she showed very distinguished love’. [25] This affection was also reciprocated by the nuns, who placed a commemorative plaque (fig. 2) in her honour in the sacristy of their church [26] as a sign of gratitude for what they received from that “queen” in both moral and material terms. The plaque is now kept at the Province of Italy Ursuline Sisters Roman Union in Rome, placed on a wall of a room on the ground floor:

CLEMENTINAE SOBIESKI MAGNAE BRITANNIAE

REGINAE

QVOD SVA DIVTVRNA COMMORATIONE PRAECLARISQUE

VIRTVTVM EXEMPLIS MONASTERIVM CELEBRIVS REDDITVM

DIGNIS REGALI SVA LIBERALITATE DONARIIS CVMVLAVERIT

MARIA IOSEPHA DE MIDDELBORG [27] PRAESES ET MONIALES

GRATI ANIMI MONIMENTUM POSVERE ANNO – D – MDCCXXXIV [28]

2. Memorial plaque dedicated to Maria Clementina Sobieska,

Rome, Province of Italy Ursulines Roman Union, 1734.

Two plaster busts [29] are preserved in the same building, one of Sobieska - which is unicum to this day - and the other of Clement XII (figs. 3-4), who wanted solemn obsequies for the queen. [30]

Having abandoned the convent in Via Vittoria, Maria Clementina continued her life in Rome in a turbulent manner, but thanks to her devotion, great modesty and dignity she entered the hearts of the Pope and the Romans and always enjoyed great respect and consideration. The Ursuline sisters suffered greatly at her death, but were able to continue to benefit from James III's visits even after the loss of the queen: ‘the Lord soon wished to crown her in Paradise, while after a few years she died, to the infinite sorrow of all, especially of this Community, His Majesty the King continued to favour coming twice a year to the Monastery feasts’ [31] (fig. 5).

5. Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L'Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l'an 1688, Rome, AGUUR, Ad 4, Via Vittoria.

The two busts, jealously preserved over the centuries by the Ursuline sisters, have been restored thanks to the contribution of the National Institute of Polish Cultural Heritage Abroad “Polonika”, and will be on display from 11 June to 21 September 2025 in Rome at the Musei Capitolini, Palazzo Caffarelli - rooms on the 3rd floor.

By Emanuela Lauro, Ph.D, General Archivist

__________________________________

1 Scholars do not agree on the exact place and date of birth. Aleksandra Skrzypietz, thanks to documentation from Rome and Minsk, establishes the birth in Oława on 17 July 1701 (cf. Skrzypietz Aleksandra, Maria Clementina Sobieska's Childhood, in Breccola Giancarlo, Ceci Francesca (eds.), Il matrimonio di Giacomo III Stuart e Maria Clementina Sobieska: 1 settembre 1719 a 300 anni dalle nozze regali di Montefiascone, proceedings of the conference (Montefiascone, 30 November 2019), Terni 2020, pp. 17-40.) A letter of January 1732, addressed by Jakub Sobieski to Father Pietro Martire Cangiassi, confirms the date of 17 July 1701; see in this regard Quesada Maria Antonietta, Né regina, né santa: Maria Clementina Sobieska, in Scritture di donne. La memoria restituita, proceedings of the conference, Roma, 23-24 March 2004, edited by Marina Caffiero and Manola Ida Venzo, Rome 2007, pp. 244-245.

2 Cf. Gaetano Platania, La fuga da Innsbruck a Roma di Maria Klementyna Sobieska Stuart, in From East to West. Women journey in the early modern period to Italy (XVII-XVII centuries), in Eastern European History Review, Special issue, n. 6/2023, edited by Jarosław Pietrzak, Viterbo 2023, p. 90.

3 On the way the marriage was signed, see Gaetano Platania 2023 cit., pp. 75-102, in particular pp. 77-82; on Clementina's flight from Innsbruck to Rome, see Platania 2023, pp. 75-102; Ceci Francesca, Memorie dei viaggi di Maria Klementyna Sobieska Stuart da Innsbruck al Lazio settentrionale, in From East to West. Women journey in the early modern period to Italy (XVII-XVII centuries), in Eastern European History Review, Special issue, no. 6/2023, edited by Jarosław Pietrzak, Viterbo 2023, pp. 103-122.

4 Cf. Platania 2023 cit., p. 90 footnote 61.

5 Cf. Chracas, No. 291, 20 May 1719, p. 14.

6 On Clementina's life in Rome and more generally on the Sobieskis in Rome, see, among others: Boccolini Alessandro, Ceci Francesca (eds.), The Sobieski family: history, culture and society : insights between Rome, Warsaw and Europe, Viterbo 2020; Chrościcki Juliusz, Flisowska Zuzanna, Migasiewicz Paweł (eds.), I Sobieski a Roma. La famiglia reale polacca nella Città Eterna, Warsaw, Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2018.

7 Several contributions have been written on marriage. See, among others, Chrościcki Juliusz, Flisowska Zuzanna, Migasiewicz Paweł (eds.), I Sobieski a Roma. La famiglia reale polacca nella Città Eterna, Varsavia, Muzeum Pałacu Króla Jana III w Wilanowie, 2018; Pietrzak Jarosław, Wife for the Pretender. Concerning the marriage between Maria Clementina Sobieska and James Francis Edward Stuart 1718-1720, in Eastern European History Review, 2, 2019 pp. 37-47; Platania Gaetano, La politica europea e il matrimonio inglese di una principessa polacca: Maria Clementina Sobieska, Manziana (Roma) 1993.

8 The former convent is today the seat of the Accademia di Santa Cecilia. With the advent of Rome's capital and the dissolution of the religious corporations, the Reale Accademia di Musica, which had been slowly advancing away at the convent's premises for some time, took over definitively in 1876 (cf. Rio Marie-Benedicte, osu, Histoire et spiritualité des Ursulines, Rome 1989-1990., p. 342). A few sisters still resisted for a long time, occupying some rooms, until in 1896 they moved to the community at 34 Via Nomentana (already 22); the last 3-4 sisters were expelled between 1900 and 1901, when the evacuation of the monastery was ordered.

9 On Laura Martinozzi see Martinelli Braglia Graziella, La duchessa Laura Martinozzi d’Este e le Orsoline: un matronage tra Modena, le Fiandre e Roma, in «Atti e memorie», serie XI, vol. XLV, 2023, pp. 221-240 and bibliography.

10 Cf. Rio 1989-1990 cit., pp. 308-309.

11 Manuscript copy of Innocent XI's Brief of 24 February 1688 is kept in Rome at Archives Générales des Ursulines de l'Union Romaine (henceforth AGUUR), Ad 4, Bref d'érection du Monastère de via Vittoria 24 février 1688, fols. n.n.

12 Cf. AGUUR, Ad 4, Notizia dell'origine e stabilimento dell'istituto delle religiose Orsoline, del loro fine particolare, e della fondazione del monastero del sudetto istituto in Roma, in Roma, per Antonio de' Rossi alla Piazza di Ceri 1718, in particular pp. 8-13. On the foundation of the monastery see also: Relazione istorica della fondazione dei quattro monasteri claustrali esistenti nello Stato Pontificio cioè di Roma, Calvi, Stroncone e Benevento. Dedicated to the Holiness of H.H. Pope Pius VII by Monsignor Filippo Terzago, Roma MDCCCII, dal Desideri a S. Antonio de' Portoghesi, pp.1-3; Masetti Zannini Gian Ludovico, Dalle Fiandre a strada Vittoria. Le prime Orsoline claustrate a Roma (1684), in ‘Strenna dei Romanisti’, 1985, pp. 409-424; Annaert Philippe, Le tricentenaire du collège des ursulines belges de Rome (1684-1984), in Bulletin de l'Institut historique belge de Rome, t. 53-54, 1983-1984 (1985), pp. 305-314; Annaert Philippe, Le voyage à Rome de la Mère Mignon. Une ursuline de Huy traverse les alpes, en 1732, in ‘Annales du Cercle Hutois des Sciences et Beaux-arts’, 1995, pp. 21-37.

13 Cf. Platania 2023 cit., p. 91.

14 On ceremonial, see for example De Carli Ferruccio, La corte pontificia e il cerimoniale delle udienze, Rome 1951.

15 Some payments in September refer to work or hire of materials for the four months that Maria Clementina stayed at the Ursulines, thus from May to September 1719. Cf. Archivio di Stato di Roma (henceforth ASR), Recapiti del Conto a' parte delle spese fatte per il Re' d'Inghilterra dalli 7 Gennaro 1719 a tutto lì 24 Gennaro 1721 dal n° primo fino al n° 92, Clemente XI°, Signor Lelmi Depositario, Camerale I, b. 2017bis, fasc. 13/7 (already reported in Quesada 2007 cit, pp. 234-235, footnotes 8-9); ASR, Entrata ed uscita della Maestà di Giacomo 3° Re d’Inghilterra dal 7 giugno 1719 a tutto il 24 gennaio 1721, Camerale I, b. 2017bis, fasc. 13/8.

16 AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, pp. 76-77; see also Angelini Gennaro, I Sobieski e gli Stuart a Roma, in La rassegna italiana, 2 (1883), Roma 1883, pp. 20-21.

17 Chracas, No. 291, 20 May 1719, pp. 15-16.

18 Maria Clementina's piousness is known and remembered from several sources. See, for example, AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L'Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l'an 1688, p. 76: ‘her beauty and kindness enamoured everyone, and to go up to her rooms one could see the little chapel of Our Lady of Loreto, so she threw herself on her knees to honour Mary Most Holy, then as much as she took high conviction of the virtue and devotion of this great Princess’; see also Angelini 1883 cit, p. 20; La contessa di Albany per Alfredo di Reumont, traduzione dal tedesco di Augusto di Cossilla, Genova 1888, p. 67: ‘Her religion starts from the heart’; Leonardo da Porto Maurizio, Opere complete di S. Leonardo da Porto Maurizio, Missionario Apostolico, Minore riformato, vol. V, 5 vols. Venice 1869, p. 39: ‘the most pious queen’; Gori Severino, Alcuni capitoli inediti della vita di Clementina Sobieski-Stuart scritti da San Leonardo da Porto Maurizio, in ‘Studi francescani’, 62, 1965, pp.235-263.

19 Cfr. Chracas, No. 307, 24 June 1719, p. 11.

20 Chracas, No. 319, 22 July 1719, pp. 23-24.

21 Cf. Cantata per il giorno natalizio della Sacra Reale Maestà Britannica di Clementina Regina d’Inghilterra […] dedicata a Sua Maestà Britannica da Monsignor Francesco Bianchini Cameriere d’onore di Nostro Signore, Roma 1719.

22 AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77.

23 Cf. Chracas, No. 337, 2 September 1719, p. 22.

24 Ivi, p. 24.

25 AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77. See also Angelini 1883 cit., p. 22.

26 The church of St Joseph and St Ursula, attached to the convent, was very dear to Clementina, who used to take refuge there often. See Platania Gaetano, Viaggio a Roma sede d’esilio (sovrane alla conquista di Roma, secoli XVII - XVIII), Rome 2002, footnote 40, p. 112.

27 Marie Joseph de Middelborg, was the fourth superior of the monastery, in charge until about 1739. Cf. AGUUR, Ad 9, Supérieures de Via Vittoria, f. n.n.

28 ‘In the year of our Lord 1734, the Mother Superior Mary Joseph of Middelborg and the nuns bore witness of gratitude in honour of Clementine Sobieski, Queen of England, because by her long stay and glorious examples of virtue she filled the monastery with gifts worthy of her royal generosity, making it more distinguished’.

29 The plaque and the two busts must have been transported to their present location between 1896 - the date of the definitive transfer of the community of Via Vittoria to the community of Via Nomentana 34 ( previously 22) - and 1900, when the Ministry of Grace and Justice General Directorate of the Fund for Worship arranged for the eviction of the monastery and the related removal of the sisters' property (cf. OSU Provincia d'Italia Archivio Storico, Fondo Roma 34, b. 1 RM 34, fasc. Ricordi dell'espulsione della comunità di via Vittoria, fol. n.n.). Amy Vitelleschi speaks of several tablets placed in the walls to commemorate Clementina's passing (Vitteleschi Amy, A Court in Exile, I, London 1903, p. 103), these tablets have not been traced to date. The bust has been published by Bindelli (Bindelli Pietro, Enrico Stuart Cardinale Duca di York, Associazione Tuscolana “Amici di Frascati”, Frascati 1982, pp. 25-28) but without any further study. See also The Jacobite Heritage (http://jacobite.ca/gazetteer/Rome/UrsulineConvent.htm); Ceci Francesca, Memorie dei viaggi di Maria Klementyna Sobieska Stuart da Innsbruck al Lazio settentrionale, in From East to West. Women journey in the early modern period to Italy (XVII-XVII centuries), in Eastern European History Review, Special issue, n. 6/2023, edited by Jarosław Pietrzak, Viterbo 2023, p. 104 and footnote 7.

30 On the funeral of Maria Clementina see, among others: Paoli Sebastiano, Solenni esequie di Maria Clementina Sobieski regina dell'Inghilterra celebrate nella chiesa di S. Paterniano in Fano dall'Illustrissimo e Reverendissimo Monsignor Giacomo Beni vescovo della città li 23 maggio MDCCXXXV, Fano, Gaetano Fanelli Stampator Vescovale e del S. Uffizio. Uffizio; Parentalia Mariae Clementinae Magnae Brittanniae, Franciae et Hiberniae Reginae issu Clementis XI Pontifex Maximus, Roma appresso Giovanni Maria Salvioni, 1736; Di Reumont 1888 cit, p. 84; Chracas, No. 2736, 16 February 1735, p. 12.

31 AGUUR, Ad 4, Chroniques Via Vittoria 1688-1847, L’Établissement des Religieuses de Sainte Ursule à Rome l’an 1688, p. 77.

Photo credits

Figs. 1-5 AGUUR © courtesy of the General Archives of the Ursulines of the Roman Union ©.